You might think the Great Barrier Reef is just a postcard-perfect stretch of coral teeming with tropical fish. But what is the formation history of the Great Barrier Reef? That tale spans over 20 million years, and it’s as layered as a sandstone escarpment in the Top End. The Great Barrier Reef isn’t just Australia’s pride — it’s the planet’s biggest living structure. But the tale behind this coral reef isn’t a quick one. It’s a geological saga that started long before we were boiling the billy or dodging stingers in the shallows. I’ve snorkelled these waters, chatted with Traditional Owners, and stood wide-eyed at coral bommies that stretch down like underwater skyscrapers. So let’s rewind the clock — way back — and unpack how this living wonder rose from ancient sea beds, survived ice ages, and continues to shape (and be shaped by) this coastal plain we call home.

It All Started 600,000 Years Ago

You wouldn’t know it, swimming around a coral cay today, but this reef’s story goes back at least 600,000 years — possibly even two million, depending on which chunk of limestone you poke.

That’s right — the reef we see today is just the latest version in a long chain of reef structures. As sea levels rose and fell through the ages, old reefs were buried under layers of sand and mud, and new ones sprang up over their remains. Like an onion made of calcium carbonate and marine critters, the reef’s built on the bones of its ancestors. This ongoing layering reveals key phases of reef development, according to the Queensland Museum and Geoscience Australia.

Australia’s Continental Shelf

Here’s where things get especially Aussie — the continental shelf off Queensland’s east coast plays the lead role in this geological drama. This wide, shallow shelf stretches up to 250 kilometres out to sea, providing the perfect depth for coral growth when conditions are right.

And right they were. When sea levels stabilised around 6,000 to 8,000 years ago, the current reef really hit its stride. The shelf let coral colonies expand laterally, forming the 2,900 individual reefs and 900 continental islands and cay islands we now call the Great Barrier Reef. Think of the shelf as the stage, and the soft corals as the cast — they just needed the curtain to rise on warm, shallow water.

With so many spots to choose from, check out our guide to the best islands of the Great Barrier Reef to see which ones fit your vibe.

Glacial Cycles

Here’s a twist — the reef you see today has been built up, smashed down, and rebuilt again more times than your uncle’s tinnie.

During the ice ages, sea levels dropped by up to 120 metres, exposing parts of the continental shelf and killing off coral communities that depended on submerged conditions. Glacial periods were bad news for coral — too cold, too dry, and definitely not enough water where it was needed.

But each time the glaciers melted, sea levels rose and coral returned, climbing upwards to stay close to sunlight. It’s like a coral elevator — one that takes thousands of years to ride to the top. These cycles of destruction and rebirth are etched into the limestone layers and studied by outfits like the CRC Reef Research Centre and the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Tiny Architects with a Big Legacy

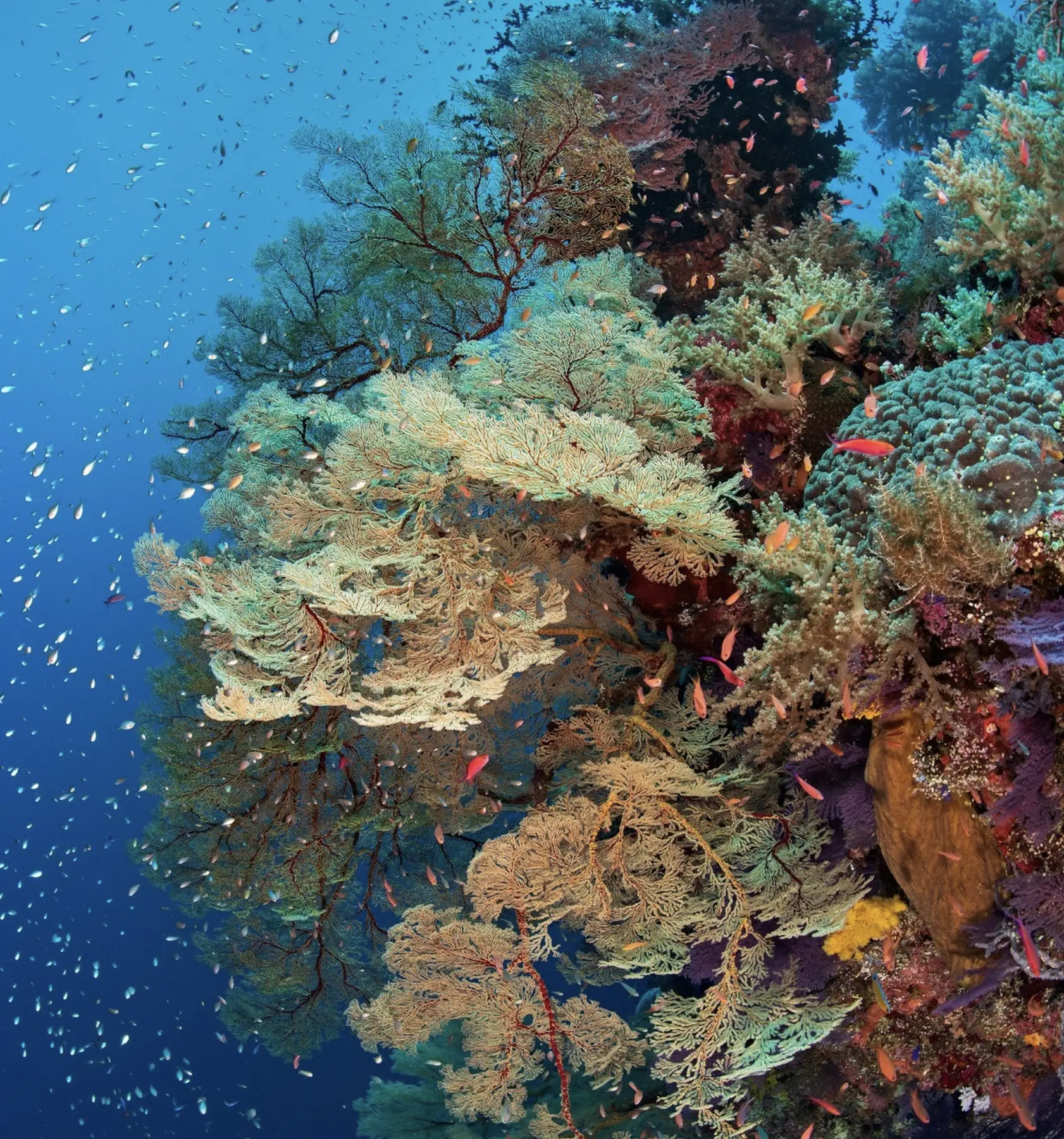

Now, let’s talk about the real heroes: coral polyps. These tiny, tentacled creatures are the stonemasons of the reef ecosystem, laying down calcium carbonate skeletons that, over generations, become vast reef structures.

It’s not all glamour — these critters are picky. They like warm, clear, low-nutrient water, steady salinity, and plenty of sunlight. They also work symbiotically with zooxanthellae — microscopic algae that live inside their tissues and help them photosynthesise. That’s what gives healthy coral its colour. This complex environment supports a massive variety of species—have a squiz at our breakdown of the marine life on the Great Barrier Reef for the full lineup of who’s who under the high tide.

Kill the algae, and the coral bleaches. That’s coral bleaching — a warning siren for ecosystem stress. Some of the worst bleaching events on record have been documented by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and Reef scientists working on the Reef 2050 plan.

The Role of River Systems and Sediment

Now we’re getting muddy — literally. River systems draining into the reef lagoon bring nutrients, freshwater, and sediment, all of which can be a blessing or a curse.

- Sediment runoff smothers coral polyps.

- Excess nutrients fuel algal blooms.

- Flood plumes reduce sunlight penetration.

Big rivers like the Burdekin, Fitzroy, and Tully have always impacted reef health. But it’s the increased agricultural activities, commercial activity, and disposal activity since colonisation that’s tipped the scales in the last couple of centuries. Still, rivers also bring life, feeding the mangroves and seagrass meadows that fringe the reef’s coast and influence the marine environment.

From Coral Colonies to 2,900 Individual Reefs

One coral colony might look like a colourful brain or spiky antlers — but scale that up over millennia and you get 2,900 reefs, 400 coral species, and more fish species than the Sydney Fish Market’s got recipes.

These reefs aren’t uniform. You’ve got:

- Fringing reefs hugging coastlines

- Platform reefs sitting on submerged plains

- Ribbon reefs curving along the edge of the continental shelf

- Crescentic reefs shaped like reef rings in deep water

- Patch reefs dotting the shallows like stepping stones

It’s not one continuous barrier. It’s a massive mosaic, stitched together by evolution and time, and documented in places like the Handbook for the Great Barrier Reef and the Barrier Reef Outlook Report.

It’s a massive natural mosaic that’s earned its place on the global stage. But is the Great Barrier Reef a 7 wonder of the world? You might be surprised at how it stacks up against the other icons.

Big Bang Moments

Let’s pinpoint a few of the reef’s turning points — the kind of big bangs that shaped its past (and maybe its future):

- Last Glacial Maximum (about 20,000 years ago): The Reef was exposed, and many coral species died off

- Rapid sea-level rise (14,000–6,000 years ago): Coral growth exploded

- Stabilised sea levels (~6,000 years ago): Formation of today’s reef structure

- Cyclones, bleaching events, crown-of-thorns outbreaks: Natural stress tests that reshuffle the deck every few decades

The reef’s no fragile snowflake. It’s robust, but even this titan has its limits. The Department of the Environment and Heritage and the Environment Protection Agency have long studied these big shifts.

Add Your Heading Text Here

Long before scientists poked at coral cores, Australia’s First Nations peoples had deep relationships with this marine ecosystem.

Traditional Owners from groups like the Yirrganydji, Gurugulu, Wulgurukaba, and Meriam Mir (a Torres Strait Islander group) have fished, travelled, sung about, and cared for the reef for tens of thousands of years.

Their stories — passed through songlines and Dreaming — describe sea-level rise, changes in reef habitats, and marine life migrations. That’s oral science, long before white coats arrived.

Modern reef management increasingly acknowledges this, and rightly so. We can’t protect the reef without listening to the people who’ve lived alongside it since the Dreaming, many of whom are Aboriginal Australian or Torres Strait Islander. Their knowledge is core to every heritage management plan and land management practices on Country.

Natural Disasters That Shaped the Reef

We like to blame humans for reef damage (and we’re not off the hook), but nature’s had her fair share of swinging too:

- Cyclones: These powerful storms flatten coral gardens but can also clear algae and rejuvenate some zones.

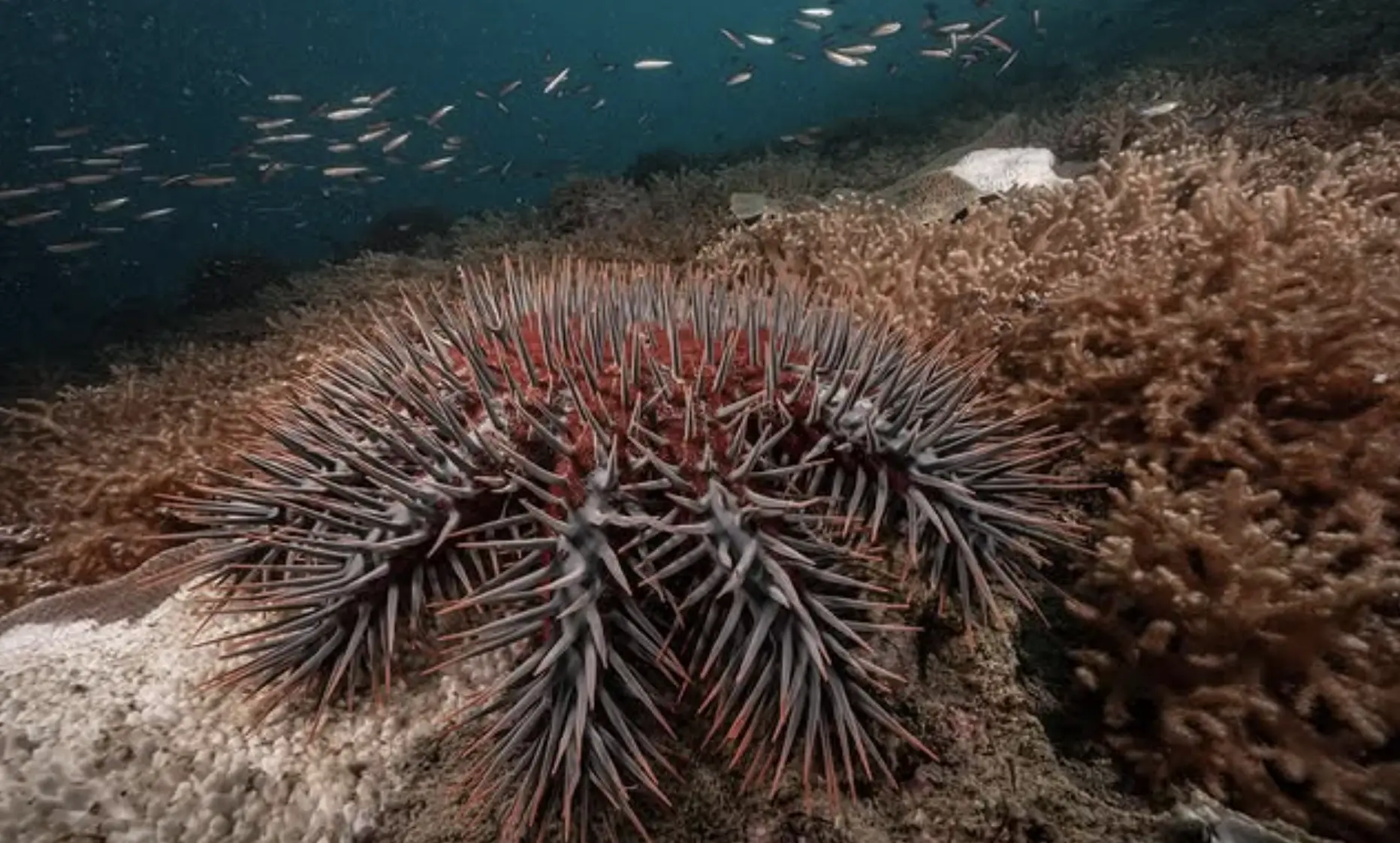

- Crown-of-thorns starfish: Native predators whose outbreaks can devastate coral cover.

- Mass coral bleaching: Triggered by rising sea temperatures in 2016, 2017, and 2020 were doozies, with black band disease and other coral disease prevalence on the rise.

The reef’s always adapted, but what’s the difference now? These disasters are coming closer together and piling on, according to the Australian Centre for Tropical Freshwater Research.

The reef’s resilience is a lifeline for its oldest residents. If you want to see these ancient mariners for yourself, check out our guide on where to find turtles at the Great Barrier Reef.

The Reef’s Past Holds Clues to Its Future

If the reef’s past is any clue, it’s a master of comebacks. It’s lived through rising seas, falling seas, meteor impacts, and shifting continents. But this time’s different — the rate of change is fast and human-driven.

Sea temps are rising, water quality is slipping, and we’re pushing species to the brink. The reef’s old tricks might not be enough unless we give it room to bounce back. We’re talking action through chemical management practices, effective management action, and continued support for the Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (also noted by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority).

The good news? The reef is still alive. Still spawning. Still dazzling. And still worth every ounce of our protection.

Protection and Preservation

Enter Reef 2050 — the Aussie government’s plan to manage, protect, and sustain the reef through to the mid-century mark. It’s not just fluff. It’s a comprehensive framework involving:

Barrier Reef Marine Park and Long-term Monitoring

Partnerships with Traditional Owners

Australian Government Productivity Commission reviews

Queensland Government and Commonwealth of Australia collaboration

Management of tourism and community initiatives

And boots on the ground — or fins in the water — from rangers to researchers, tourist boats to turtle taggers. Even green turtles and marine turtle conservation form part of the Reef 2050 action network.

Ready to see history in the making?

The reef’s story spans millions of years, but your holiday is just beginning. To make sure you’re visiting the right spots at the right time, head over to our expert advice on how to choose a Great Barrier Reef tour and start your own adventure.