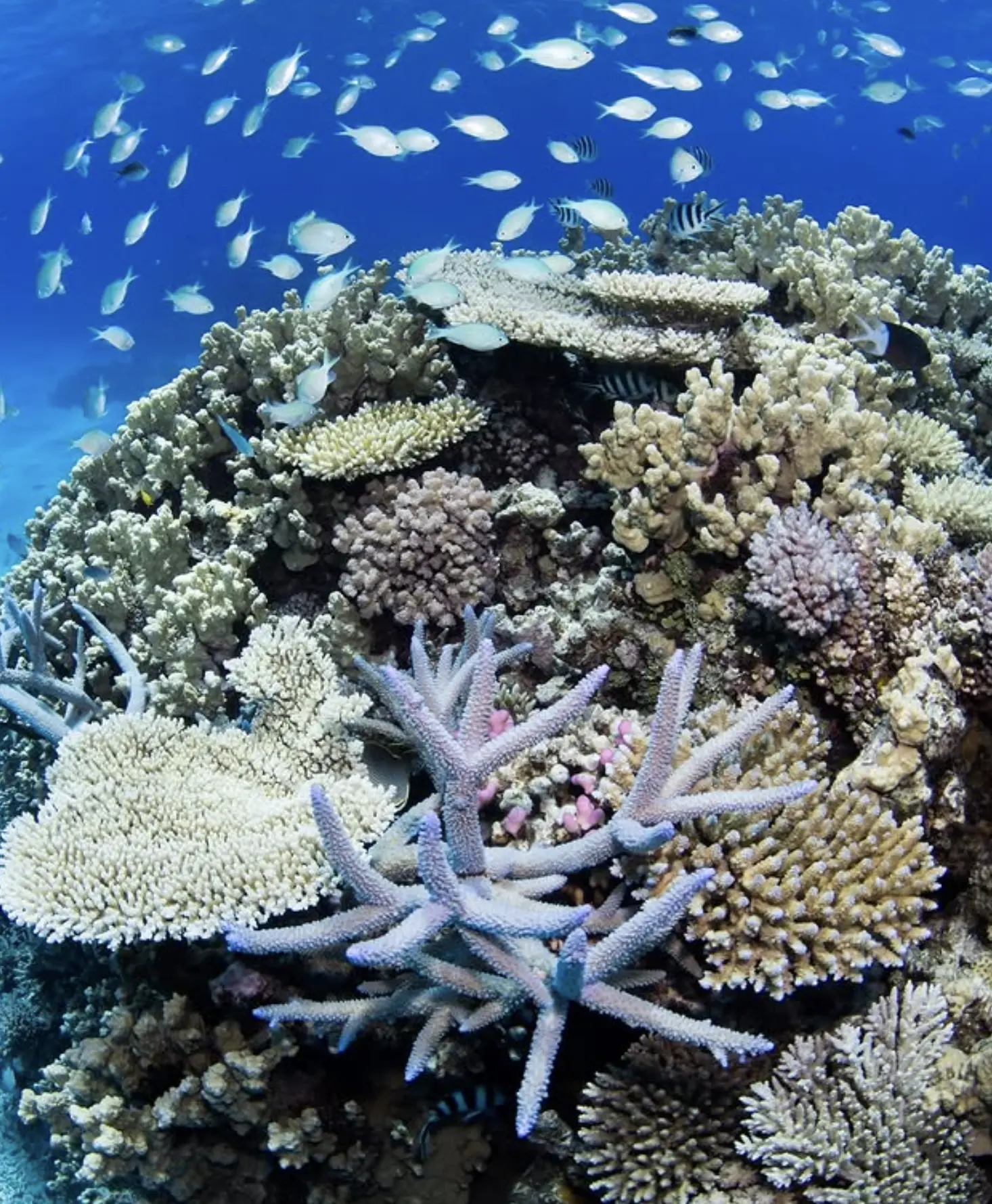

The flora of the Great Barrier Reef forms the backbone of this vast ecosystem, shaping marine habitats, cleaning the water, and holding up entire reef food webs. Most folks come to the Great Barrier Reef chasing clownfish, coral gardens, and maybe a cheeky sea turtle. But if you’ve only got eyes for the big and flashy, you’re missing half the picture. The reef vegetation — from seagrasses to salt marshes — quietly holds the whole ecosystem together. It feeds turtles, shelters juvenile reef fish, and even helps keep those iconic coral formations from dying.

And no, it’s not all just marine algae and slime. Let’s get into it: what coastal and marine plants actually include, why it’s more important than you’d think, and where (and when) you can spot it in full bloom.

What Plants Call the Reef Home

It’s not your average rainforest garden

When we talk about “flora” on the Great Barrier Reef, we’re not just chatting about underwater plants. Technically, many aren’t plants at all — not in the land-dwelling, chlorophyll-packed, leaf-and-root kind of way.

Here’s what counts:

- Seagrasses – Actual flowering plants with roots, leaves, and even seeds. These true plants grow in seagrass beds across shallow waters and deeper waters along the continental shelf.

- Mangroves – Coastal trees that straddle land and sea. Mangrove plants and the many species of mangrove play a crucial role in coastal waters and internal waters.

- Algae – Not true plants, but they photosynthesise like champs. Think Green algae, Brown algae, turf algae, and even the quirky Bubble algae.

- Phytoplankton – Microscopic life that fuels the entire marine food web. These photosynthetic life forms are a vital part of marine ecosystems.

- Saltmarshes – Semi-aquatic habitats are often overlooked in favour of shinier reefs.

Why Reef Flora Matters

No plants, no reef

You could say the reef flora are the unsung heroes. While everyone’s cooing over coral polyps, it’s the algae and plant-like crew doing much of the heavy lifting:

- Producing oxygen and playing a major role in carbon sequestration

- Trapping sediment so the reef doesn’t get smothered

- Providing food for turtles, dugongs, herbivorous fish, and invertebrate animals

- Offering nursery habitat for juvenile marine species and reef organisms

- Soaking up carbon dioxide — yep, they help tackle climate change too

Without these green machines, the coral reef systems would unravel faster than a mozzie net in cyclone season.

Green Holds the Reef Together

From coral islands to volcanic island outcrops, every stretch of the reef is alive with plant-like life. Whether it’s marine algae clinging to coral structures or salt marshes whispering to mangroves, these elements play a vital role in every corner of the Great Barrier Reef.

Ignore them, and you’re only seeing half the story.

Seagrasses: Reef Pastures for the Big Mobs

Turtle tucker and dugong delis

Seagrasses are the only true flowering plants that live fully submerged in salt water. There are around 15 species of them on the Great Barrier Reef, forming extensive seagrass meadows in the shallows and outer reef areas.

Why should you care?

- Green turtles and dugongs depend on them for dinner — they’re a major food source.

- Juvenile fish, including species of shark and species of fish, hide out in the blades.

- They stabilise sediment and improve water quality.

You’ll find stunning seagrass beds off Heron Island, Green Island, and around Strait Island and North Stradbroke Island. These areas are part of the Queensland Marine Park and National Park networks, which help protect the reef’s biggest living structure.

Mangroves: The Reef’s Coastal Shield

Mud, mozzies, and more meaning than you realise

Mangroves might look like gnarled old trees growing out of swampy flats, but they’re ecological powerhouses. With over 30 mangrove species and their supporting mangrove plants, they form dense buffer zones between the sea and land.

Here’s their greatest hits list:

- Storm protection during tropical cyclones

- Erosion control and protection for coral reef formation

- Nurseries for reef sharks, fish, and crustaceans

- Carbon sinks storing more carbon than most terrestrial plants

Hot tip: Hinchinbrook Island has one of the best mangrove systems around, sitting just off the continental islands and buffering the coast’s internal waters. Be prepared for mozzies and muddy boots.

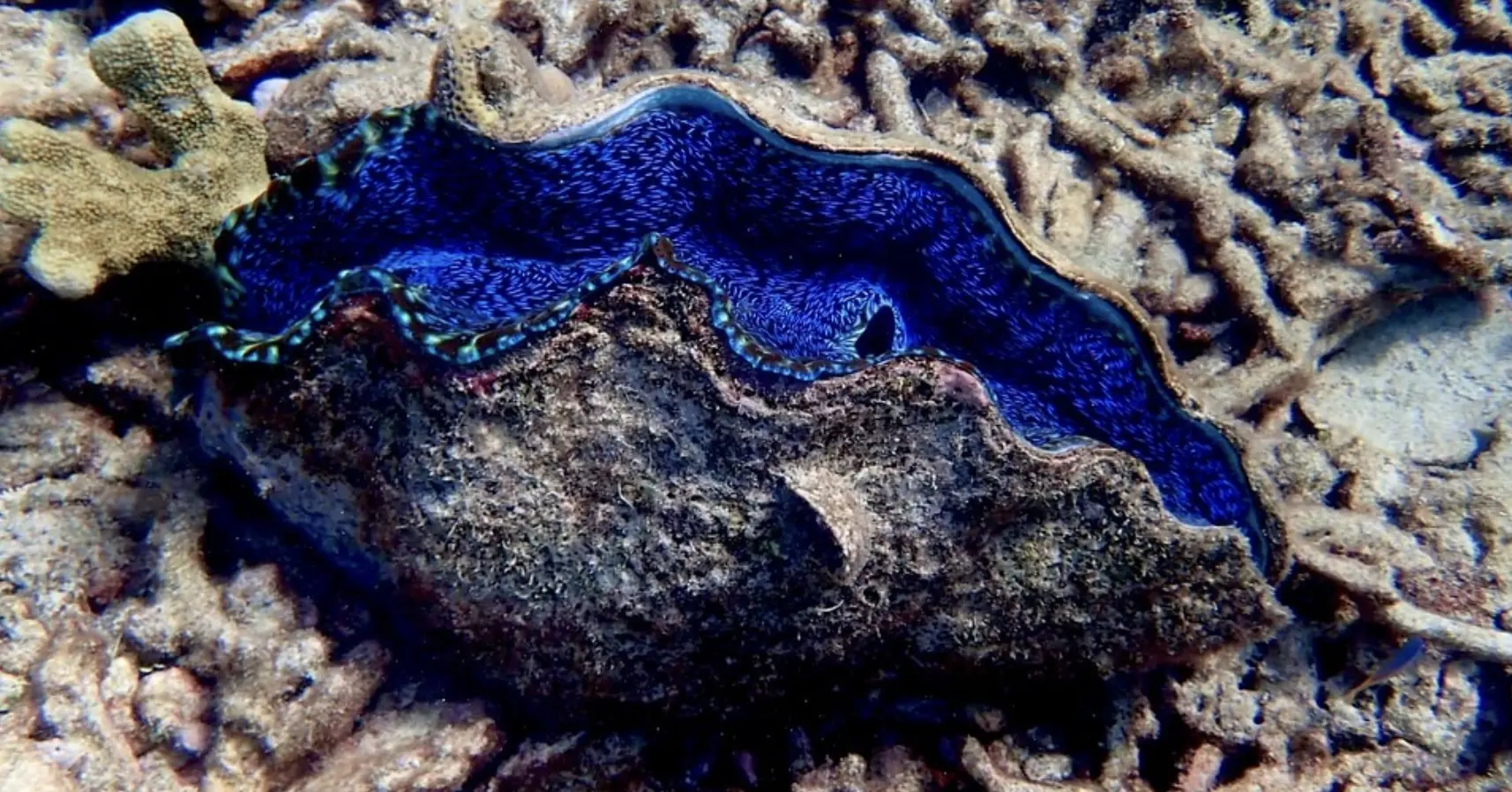

Algae: Not Just Slime on Rocks

From food to coral ally

Algae get a bad rap. People picture green gunk clinging to boat hulls. But marine algae like turf algae, Green algae, Brown algae, and soft coral symbionts are critical to reef growth.

They:

- Provide oxygen

- Feed marine animals

- Form the base of the food chain

- Support coral reef formation by feeding coral polyps

- Help repair dead coral after stress events like coral bleaching

Coral bleaching is a hot topic (literally), and algal species play a vital role in helping reef organisms recover post-mass bleaching event. Algae support coral larvae and coral growth by maintaining the reef structure.

Phytoplankton: The Microscopic Powerhouse

Tiny but mighty

These individual organisms aren’t flashy, but they’re major players in primary production on the reef. Floating in shallow reef and outer shelf zones, phytoplankton support marine sanctuaries from Hardy Reef to Hoskyn Island.

They:

- They are a primary food source for invertebrate animals and species of whales

- Help indicate shifts in ocean temperatures and water mark levels

- Support biodiversity and sustainable fishing practices

Phytoplankton blooms can reflect water quality — a shift in their balance may signal unsustainable fishing practices or runoff impacts. Watch this space in the 5-year Climate Change Action Plan.

Saltmarshes: The Overlooked Fringe

Where the land whispers to the sea

Salt marshes are low-lying native plants adapted to brackish and saline conditions. Often found on the fringes of coastal wetlands and estuaries, they play a crucial role in linking terrestrial plants and marine ecosystems.

Benefits:

- Act as natural filters, catching runoff

- Support wading birds and small marine life

- Create a habitat for turtle species and juvenile fish

You’ll find salt marshes thriving in less-trafficked parts of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, often hidden behind mangroves or tucked into small coves.

Tips for Flora-Focused Reef Adventures

- Use reef-safe sunscreen — help maintain water quality and avoid harming coral larvae

- Don’t walk on shallow reefs or trample seagrass beds

- Stick to designated patch reefs and guided walks in Marine Park zones

- Ask Traditional Owners about natural wonders and cultural connections to reef flora

- Pack field guides to ID 300–350 species of seagrass, 4–500 species of algae, and 5,000–8,000 species of marine organisms

When’s the Best Time to Explore?

Best time: Dry season (May to October)

- Clear water means easier spotting of marine plants and coral reef systems

- Lower tides expose mangrove roots and salt marsh edges

- Reduced runoff = healthier seagrass beds and algal coverage

Avoid: Wet season (Dec to March)

- Cyclones, muddy coastal waters, and mass bleaching events

- High sedimentation smothers coral and marine algae

Some flora sites sit inside the 100,000 square kilometre net-free oasis zone — part of the reef’s broader reef conservation and Marine Park protections.

FAQ

Are there real plants in the Great Barrier Reef?

Yes — seagrasses and mangroves are true plants. Algae and phytoplankton aren’t technically plants, but function like them through photosynthesis.

Where can I see reef flora up close?

Try Heron Island, Green Island, Hinchinbrook Island, or Hoskyn Island. You’ll find mangroves, seagrass beds, and shallow water algae systems — all in top condition during the dry season.

How do marine plants help prevent coral bleaching?

By stabilising sediments, reducing nutrient runoff, and supporting coral growth, marine flora improves reef resilience to stress and high water temperatures.

What’s the link between reef flora and food sources?

They’re a major food source for marine turtles, herbivorous fish, reef sharks, and species of whales, supporting access to food sources for all levels of reef life.

Why should we care about reef flora?

They’re essential for carbon sequestration, reef structure, fish nurseries, and overall reef conservation. Without reef flora, coral reef ecosystems would collapse.